A town called Church Population: 111,600

***Kilis was hit by the earthquakes of 2023. I have no information yet on the damage done to its historic monuments.***

Right on the border with Syria, Kilis is a town that has been changed beyond all recognition by the Syrian War. Before that it was a routine crossing point for travellers from Aleppo. Afterwards it became a town of asylum for those fleeing the carnage. It has grown enormously in a decade and almost all the incomers are Syrian.

Kilis used to be a town of small pleasures. The Ulu Cami aside, there are no major monuments to enjoy here. On the other hand there are any number of lovely old mosques and hamams (Turkish baths) down the back streets, not to mention a surprising number of narrow alleyways lined with old houses that gently evoke the grander delights of Şanlıurfa or Gaziantep.

The modern parts of Kilis may look much like those of any other Turkish town but this is a place which still cleaves to tradition, in particular to its own cuisine. In one of the many kuruyemiş (fruit and nut) shops about town you might want to buy some of the local variety of sucuk, strings of walnuts embedded in fruit jelly that dangle from the ceiling like mobiles decorating a child’s bedroom.

Don’t leave town without trying:

- katmer, a delicious pancake sandwiching walnuts, pistachios and cream

- oruk kebab flavoured with mint and garlic

- Kilis tava which is rather like a large flattened meatball decorated with tomatoes and pepper

Backstory

Backstory

Kilis’ geographical location ensured it one of those tempestuous relationships with history in which the town was forever changing hands as rampaging armies forced their way through. There’s nothing to show now for its Hittite, Roman or Persian past, and between the fifth and 11th centuries this was a part of the world right on the hotly-contested frontier between Christianity and Islam.

Eventually it was the Mamluks, a dynasty based in Egypt, that managed to secure the area and it was under the Mamluks that Kilis began to thrive as a trading centre.

But in 1516, after more than 250 years of hegemony, the Mamluks were defeated by the Ottoman Sultan Selim I, ushering in a period of peace and prosperity during which many of the town’s more impressive buildings were erected.

Around town

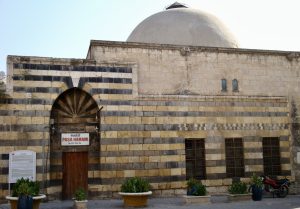

The most obvious place to start exploring is the square in front of the Canbolat Paşa Tekke Cami, just off Cumhuriyet Caddesi. To one side of this square stands the cute little Mevlevihane Cami that dates back to 1525 and was once the semahane (ritual room) of a lodge of whirling dervishes. Its stripy facade immediately evokes the architecture of Gaziantep while echoing that of nearby Aleppo (Halep) too, whereas the much larger Canbolat Cami, built only 28 years later, espouses a more familiar style of Ottoman architecture that has inevitably led to claims (unlikely to be true) that it’s a work of Mimar Sinan.

The most obvious place to start exploring is the square in front of the Canbolat Paşa Tekke Cami, just off Cumhuriyet Caddesi. To one side of this square stands the cute little Mevlevihane Cami that dates back to 1525 and was once the semahane (ritual room) of a lodge of whirling dervishes. Its stripy facade immediately evokes the architecture of Gaziantep while echoing that of nearby Aleppo (Halep) too, whereas the much larger Canbolat Cami, built only 28 years later, espouses a more familiar style of Ottoman architecture that has inevitably led to claims (unlikely to be true) that it’s a work of Mimar Sinan.

The mosque was built for Emir Canbolat, one of the powerful Canbolatoğulları family who held sway both in Kilis and Aleppo for several centuries, and replaced in importance the old Ulu Cami (Great Mosque) that had served as the main religious centre while the Mamluks governed Kilis. The Canbolat Cami retains much of its külliye, or complex of associated buildings, although the ugly şadırvan (ablutions fountain) is a modern addition it could well do without.

If you wander round it to the left you’ll come to the large Canbolat Paşa Hanı, a warehouse which smells overpoweringly of pekmez (grape molasses). That’s because it has become a storage centre for bricks of dried pekmez, a Kilis speciality made using a type of grape that can’t be eaten fresh but is instead converted into raisins and then into pekmez.

To reach the han you pass through an abbara, one of the attractive arched passageways that are usually thought of as a feature of Mardin but that also crop up in Urfa and Kilis, and indeed in most of the Middle East.

More or less in between the old dervish lodge and the mosque stands the multi-domed, men-only Paşa Hamamı, dating back to 1567 and one of many lovely baths dotted about the city.

More or less in between the old dervish lodge and the mosque stands the multi-domed, men-only Paşa Hamamı, dating back to 1567 and one of many lovely baths dotted about the city.

Turkish baths can be found all over the country, but they’re also a feature of most of the Islamic world, and the baths of Kilis are closer in design to those of Syria than to those of distant İstanbul. In particular they’re almost identical to what was the wonderful and exotic Hammam Yalbougha an-Nasry of Aleppo. That used to be a popular tourist attraction making it all the more sad that most of Kilis’ baths have been allowed to fall into dereliction.

Happily, the tide has started to turn, and the Eski Hamamı (Old Hamam), dating back to 1562 and right beside the Cüneyne Cami (Little Heaven Mosque), has been restored. The Hoca Hamamı, dating back to 1545, welcomes female bathers.

Tucked away along streets too narrow for cars to pass you’ll eventually stumble upon the Ulu Cami (Great Mosque, 1339), the city’s finest surviving example of Mamluk architecture and presumably sidelined by the Ottomans in an attempt to stamp their own image on their new acquisition. The Ulu Cami is a long, narrow building with multiple entrances onto a courtyard. Its style is usually compared to that of the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus although there are also clear parallels with the Diyarbakır Ulu Cami, itself probably based on the Umayyad Mosque. It’s an extraordinary find in such an out-of-the-way location.

Back on the main streets it’s worth seeking out the restored early 16th-century Tabakhane Cami and, nearby, one of Kilis’ more curious sights, the Öksüz Minare (Orphan Minaret), a single minaret with an enormous six-pointed star carved on its base that is all that survives from the early 19th-century Mehmet Paşa Cami complex.

Opposite the Tabakhane Cami there’s also a 19th-century covered çeşme (fountain) of the type called in Kilis (and Gaziantep) a kastel. As in İstanbul, the prosperous often showed off their wealth by providing access to drinking water for their poorer fellows. In this case the philanthropist was the little known Salih Ağa, although another such kastel near the Mer-Tur Hotel was provided in the 17th century by the grand vizier Damad Mustafa Paşa, aka İpşir Paşa who was murdered by the Janissaries in 1655.

The Kilis back streets are full of single-storey houses that have proved far too small for modern needs. The result is unfortunate in that most now boast an attractive adobe or stone-built ground floor topped off with an ugly first floor of concrete or breezeblocks.

Still, you’ll enjoy inspecting the fine decorative details of door and window frames while noting the little round apertures inserted beside the front doors to let air circulate. Every now and then you’ll also spot a beautiful cumba (bay window) with delicate wooden carvings along its frame or a gate decorated with a pattern made out of nails. Many of the houses are also adorned with metal plaques indicating that a family member has been on the Haj (pilgrimage to Mecca).

Still, you’ll enjoy inspecting the fine decorative details of door and window frames while noting the little round apertures inserted beside the front doors to let air circulate. Every now and then you’ll also spot a beautiful cumba (bay window) with delicate wooden carvings along its frame or a gate decorated with a pattern made out of nails. Many of the houses are also adorned with metal plaques indicating that a family member has been on the Haj (pilgrimage to Mecca).

Kilis Museum (closed Mondays) is housed in the imposing Neşet Efendi Konağı (1925-27) and contains the finds from the Öylüm and Leylit Höyüks (tumuli) as well as a small ethnographical collection.

Eating

The influx of refugees has resulted in the local cuisine acquiring a very Syrian flavour. Humus, falafels and foul beans are now to be found in many small lokantas, especially near the Kilis Museum.

Sleeping

Mer-Tur Hotel. Tel: 0348-814 0834

Olea Otel. Tel: 0384-813 2929

Transport info

There are buses to Kilis from Gaziantep otogar every half an hour (90 mins).

Kilis Otogar is on the south side of town.

Day trip destinations