Centre of the rose industry Population: 248,000

Market day: Wednesday and Sunday

Festival: Rose harvest, early May

Most famous son: Süleyman Demirel (1924-2015)

Midway between Lakes Burdur and Eğirdir in Western Anatolia lies Isparta, one of Turkey’s many easily overlooked inland towns. Because its name sounds so like “Sparta” it’s almost impossible for anyone brought up on the stories of Ancient Greece not to prick up their ears whenever the town is mentioned. But of course Isparta is nothing like Sparta -the name is simply a corruption of the Psidian “Baris”. Instead it’s one of those places that most travellers whisk past on their way to smaller and more immediately inviting Eğirdir.

But for anyone who does bother to stop and take a look round Isparta may turn out to be a pleasant surprise. It’s one of a growing number of small inland towns that exudes a comfortable air of self-confidence, its tree-lined streets framed sometimes by the usual dull apartment blocks but sometimes by duplexes and triplexes built on a more human scale that suggest the existence of a stable and prosperous middle class.

Around town

At first glance the town centre is not especially promising. Right at its heart in Kaymakkapı Meydanı stands a statue of Isparta’s most famous son, Suleyman Demirel, five-times prime minister of Turkey and later the ninth president, tipping his hat to passers-by in trademark fashion.

Demirel was born in the nearby village of İslamköy which duly hosts a small museum to him. Not altogether surprisingly, every other street and public building is also named after him.

Scattered around the main square are most of Isparta’s more interesting buildings. They include a pleasant, if unspectacular, Ulu Cami dating back to 1417 and the Firdevs Bey Cami which was built in 1561 and is sometimes attributed to the great Ottoman architect Sinan, as is the adjoining bedesten (covered market).

Also worth a quick look is the dainty porticoed Kavaklı Cami (Poplar Mosque) which was built in 1782-3 and incorporates some Kütahya tiles in its facade.

It’s also worth spending a few hours poking about in the back streets. Until the 1923 population exchange Isparta had a large Greek population and many of their lovely wooden houses still survive, albeit in a shocking state of neglect.

To find them you should head for Gazikemal Mahallesi, where, in street upon street of erstwhile Ottoman finery, Isparta’s poorest residents now make their homes. Many of the houses here come with tall stone walls, solid wooden gates and overhanging red-tiled roofs so that they look like country houses which have somehow strayed into town.

Amid the wreckage is one short pedestrianised street where several of the houses have been restored with varying degrees of sensitivity. In one of them the famous Islamic thinker and philosopher Said Nursi (1878-1960) lived for the last ten years of his life. His house is open to the public although the arrangements for visiting are hardly user-friendly. It’s not possible, for example, for a lone woman to enter while there are male visitors present, and women must also dress in the same way as they would to enter a mosque.

Amid the wreckage is one short pedestrianised street where several of the houses have been restored with varying degrees of sensitivity. In one of them the famous Islamic thinker and philosopher Said Nursi (1878-1960) lived for the last ten years of his life. His house is open to the public although the arrangements for visiting are hardly user-friendly. It’s not possible, for example, for a lone woman to enter while there are male visitors present, and women must also dress in the same way as they would to enter a mosque.

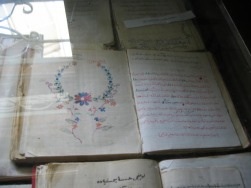

However, if you do venture inside you will find a typically Ottoman-style house which will seem surprisingly devoid of furnishings to Western eyes. On display here are are some of Nursi’s clothes and personal effects as well as a collection of his books which have been translated into numerous languages. Also preserved here are some poignant children’s books written in Arabic which were retrieved from the nearby mountain village of Barla.

Isparta has a fine local museum (closed Mondays) although its location, on a residential back street, means that virtually no casual visitor is going to stumble upon it. This is a great shame because for a small museum it houses a very interesting collection of items. (It is possible that it is still closed for restoration at the start of 2024.)

As ever, they are divided into two separate sections, one archaeological, the other ethnographic. The archaeological section houses the finds from Seleucia-in-Sidera and from the great Roman site of Adada, high in the mountains above Eğirdir, as well as an assortment of rather cute Roman gravestones.

It also showcases some vast ceramic urns from the Early Bronze Age Harmanören cemetery that were dug up during road-widening works north-west of Isparta. The dead were apparently buried inside these pots along with their most precious possessions.

For those saddened by the abject condition of the old Ottoman houses, one corner of the museum has been set up to show what their living rooms would have looked like in their heyday when they were adorned with some gorgeous wooden carvings. An upstairs gallery also displays a dazzling selection of the sort of Isparta carpets which you are unlikely to find on offer in local carpet shops today.

Yet another corner of the museum celebrates the town’s main claim to contemporary fame, the tiny pink roses which, when harvested, are used to make attar of roses, the strong-smelling oil used for perfume.

Yet another corner of the museum celebrates the town’s main claim to contemporary fame, the tiny pink roses which, when harvested, are used to make attar of roses, the strong-smelling oil used for perfume.

The roses were introduced to the area by Bulgarians who moved here in the late 19th century, bringing with them the distilling technology that they had grown up with. Today most rose oil is produced in large modern factories although it’s still possible to find it being made in old-fashioned stills in some of the surrounding villages. If you look carefully at the bits and pieces dotting the small park off Demirel Bulvarı you will recognise several battered old stills stripped of their function and turned into frippery decoration.

Down the road from the museum is Isparta Railway Station with, standing outside it, a magnificent old steam locomotive. Around the station are several fine examples of old railway architecture, including an impressive stone water tower about which the locals could provide no information at all.

Out on the east side of town near the Devlet Hastanesi (State Hospital) the remains of two enormous stone churches, St Payana and St George (1857-860), are a reminder of the Greek population that was lost in 1924.

Finally, if it’s a sunny day and you feel like picnicking it’s worth hopping on a bus and heading one km south to Gökçay Mesireliği (Gökçay Picnic Place). Here in a beautifully landscaped park are several fine restaurants as well as a lake, all offering views out over Isparta. Here, too, there is an amphitheatre where, in the first few days of May, the rose harvest is celebrated with a festival offering fireworks, folk dancing and a sprawling outdoor bazaar.

Sleeping

Basmacıoğlu Otel. Tel: 0246-223 7900

Barida Hotel. Tel: 0246-500 2525

Transport info

There are regular buses to Isparta from Konya and Antalya as well as minibuses from nearby Eğirdir (34km). Only a few transit the town centre.

The Otogar is on the outskirts of town with shuttle buses running into the centre. Local buses arrive and leave from a separate Köy Garaj, in an equally out of the way location. Getting between the two is time-consuming, making connections difficult. Despite talk of moving the main otogar out towards the eastern side of town near the Süleyman Demirel University in 2024 it was still in the same old location as far as I know.

Burdur buses leave from the main Otogar rather than the Köy Garaj. Ağlasun buses for Sagalassos leave from the Köy Garaj.

Day trip destinations

Seleucia in Sidera

Read more about the rose industry: The Pink Gold of Isparta