The big disappointment of this visit to Diyarbakır is to find so many of the things I’d visited eighteen months ago closed for restoration although of course it’s a very good sign that the authorities hope to be able to attract more visitors to the city in due course. Personally, I think that Diyarbakır has even more potential as a tourist destination than Mardin which has done so well over the last few years. After all, Diyarbakır is so much larger and, unlike Mardin, it has a range of hotels and restaurants to suit all budgets. Once the monuments have been spruced up it will have all the building blocks in place. Except the crucial one, of course, which is guaranteed peace and security. Rebecca and I may be prepared to play it by ear, but Jo Tourist is hardly going to be happy with that. What Jo Tourist wants is that there should be no more talk of rioting or tension but for that to happen lasting solutions will have to be found to the problems of the east, not least the huge problems of poverty and unemployment.

As it is there are now effectively three Diyarbakırs, only one of interest to tourists. The modern town is just another big conglomeration of shop and apartment blocks, briefly glimpsed on the road in from the bus station, while the shanty town sprawling south from the walls should be a no-go area for any outsider with sense. Instead it’s the old town hunkered down behind the brooding basalt walls that grabs all the attention.

The Ulu Cami is closed for a restoration that will see centuries of filth scraped off the wonderful colonnades ringing the courtyard. So are the Ziya Gökalp and Cahit Sıtkı Tarancı house-museums but we have better luck with the Esma Ocak Museum. Finding these house-museums is a bit like hunting for a needle in a haystack in the medina-like warren of streets in the old part of town and I can’t help but remember my first visit on my own in 1996 when I’d resorted to hiring a guide just to keep the crowds of children away from me. Naively, I thought at first that the schools must be closed. Only slowly did it dawn on me that the huge groups that mobbed me were actually individual families of up to 20 children a piece.

The house-museums are primarily interesting for their architecture with floral patterns in white breaking up the relentless grey of the stonework. All of them are centred on courtyards with rooms on different sides being used according to the season and the position of the sun. The woman who shows us round the Esma Ocak is friendly and welcoming but hers is a particularly cruel story. She has twin daughters born as test tube babies after twenty years of struggling for pregnancy. At first I just see two little girls, fresh faced and bright eyed. Only slowly does the story come out: how one was born with her intestines on the outside of the body and has already endured many operations; how she suffers from learning and hearing difficulties; how she will be unable to have children of her own. Her parents had sold their house to pay for IVF, which is why the woman works as a guide in the museum now. Does the government help you? I ask although I know even before she shakes her head what the answer will be. Yet she shows no signs of self-pity. I think of her smile, then I think of the whine of the professional beggar and cringe at the unfairness of the world.

Across the road we take a peek at Surp Agop church across the road which is in the process of being rebuilt. We’ve already dropped in on the Mar Petyun Chaldean church, beautifully restored, its huge, empty aisles a silent reminder that this part of town still had a large Christian population right up until the First World War. It’s one of those situations where a great deal is being left unsaid. The house-museums, for example, once had Armenian owners, a fact that is not exactly shouted from the rooftops.

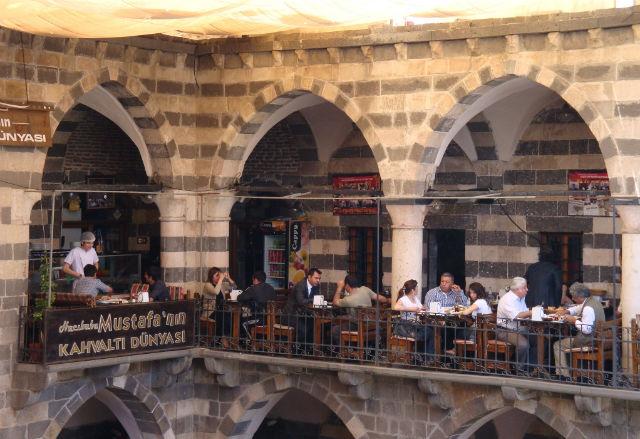

We pause for lunch at a ciğ köfte stand just inside the Mardin Gate, then take a turn round the Cheese Market before heading off in search of the Dengbej Evi, my big find of the previous visit. Here in the courtyard of another lovely old stone house I had stumbled upon a cluster of old men gathered round a table to listen to one of their number who was singing to them unaccompanied. From time to time the others would tune in with what sounded like murmurings of assent: “Yes, yes, he’s right about that, I remember it well.” As they were speaking in Kurdish of course I didn’t actually understand the words but their meaning was clear. Then they had been sitting on the verandah of the house but today they’re in a much less picturesque huddle in the courtyard itself. Dengbej, I now know, was a Kurdish tradition of story-telling in song, now being kept alive courtesy of an NGO.

The day is wearing on and we’re about through with stripy minarets and twisty, turny alleyways. There’s just one date we have left to keep and that is with Selim Usta Amca, Diyarbakır’s iconic restaurant that specialises in kaburga or stuffed lamb ribs. Three of us order a portion for two which is more than adequate. The restaurant is hardly full. On the other hand it’s not empty either. If old Diyarbakır is truly tense there’s precious little evidence of it to be seen here.

Written: 24 May 2011