Heart of the old Syrian Orthodox community Population: 85,600

Back in the 1990s the small town of Midyat hardly featured on the travel radar, being effectively cut off behind curfews, roadblocks and general anxiety about visiting the south-east of Turkey. But it was always way too good a secret to last and now its cover has been well and truly blown.

Back in the 1990s the small town of Midyat hardly featured on the travel radar, being effectively cut off behind curfews, roadblocks and general anxiety about visiting the south-east of Turkey. But it was always way too good a secret to last and now its cover has been well and truly blown.

The reasons for this are not hard to identify. Over the last twenty years the general security situation in the southeast has – despite some setbacks – improved by leaps and bounds, which means an end to most of the pesky impediments to travel. such as roadblocks At the same time the popular TV series Sıla beamed images of Midyat’s lovely honey-gold houses into sitting rooms countrywide with the result that Turkish travellers started rushing to eye up the sets for themselves.

Neighbours they may be, with a shared history and architecture but Mardin and Midyat could hardly feel more different. Where Mardin wraps itself tightly around a hillside, its streets narrow and congested, Midyat lies flat on the plain, its streets wide and inviting. And where Mardin’s churches play second fiddle to its gorgeous old mosques and medreses, in Midyat it’s the Syrian Orthodox (Suryani) churches whose towers dominate the skyline.

Both towns have large Arab populations who live alongside the Turks and Kurds. On their clocktower the Midyat authorities deploy images of a minaret (Muslim), church tower (Christian), and peacock (Yezidi) to play up the idea of local multiculturalism but in reality while there’s still a fairly sizeable Suryani community here all the Yezidis, followers of the Peacock Angel, left a long time ago.

Around town

Whichever approach you choose, your first port of call should be the wonderful Konukevi (guesthouse) which used to belong to the head of the Protestant community and stands as far uphill as a town on a plain permits. As the fussy Ulu Cami in Divriği is to the more sober Selçuk architecture of nearby Sivas, so is this house to the more modest Midyat dwellings around it – a sort of rococo twist on what is already a pretty frilly style of local stone masonry. The house is built on three levels with a courtyard on the ground floor and two spacious terraces on the upper levels which would have allowed the owner to scan his domain and peer out into the rural distance.

Whichever approach you choose, your first port of call should be the wonderful Konukevi (guesthouse) which used to belong to the head of the Protestant community and stands as far uphill as a town on a plain permits. As the fussy Ulu Cami in Divriği is to the more sober Selçuk architecture of nearby Sivas, so is this house to the more modest Midyat dwellings around it – a sort of rococo twist on what is already a pretty frilly style of local stone masonry. The house is built on three levels with a courtyard on the ground floor and two spacious terraces on the upper levels which would have allowed the owner to scan his domain and peer out into the rural distance.

The upper terrace is a good place for you, too, to peep down on the minutiae of local life. On the flat roofs you will see many curious metal platforms, the tahts or thrones on which people sleep during the heat of summer and which are raised up off the ground to keep their occupants safe from passing scorpions. If you’re lucky you may also see, hanging out to dry like sheets on a washing line, some of the locally made pestil (fruit leather) – dried and pressed fruit sometimes with nuts embedded in it – that is on sale all around town.

It’s possible to stay in the Konukevi although not in the topmost room that was once described by The Little Hotel Book as “the most gorgeous single room – in the whole country”.

Midyat is one of those places where just roaming the back streets is reward enough for the time taken to get there. And if you do want more specific sights, you can always go in search of the five old churches whose bell towers punctuate the skyline interspersed with the minarets.

Like Mardin, Midyat has a mixed cultural heriitage. Thirty years ago the residents included around 5,000 Christians, mainly adherents of the Syriac Orthodox faith, an offshoot of Orthodox Christianity which split from the mainstream in the sixth century. Since then migration to work in northern Europe in the 1980s and ‘90s, combined with the troubles in the south-east, has forced numbers down until there are only about twenty original families still living in the old Christian quarter.

Finding the four Syrian Orthodox and one Protestant church is no easy matter since they’re buried so deep amid the surrounding houses that they feel like ever-retreating mirages in the desert. Unfortunately it’s rare to find their doors unlocked even on Sundays.

Finding the four Syrian Orthodox and one Protestant church is no easy matter since they’re buried so deep amid the surrounding houses that they feel like ever-retreating mirages in the desert. Unfortunately it’s rare to find their doors unlocked even on Sundays.

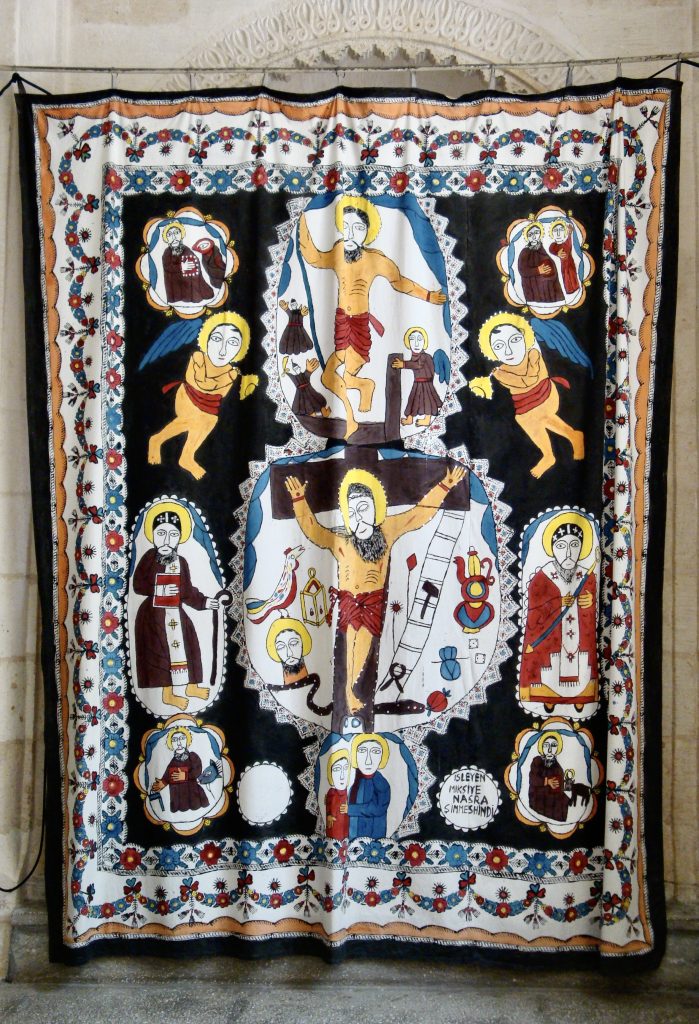

If you’re lucky enough to get inside any of the Suryani churches you’ll find them newly restored and decorated with the same brightly painted wall hangings as can be seen in Mardin, an art form that is now on its very last legs. In one church, an informal school teaches children Turoyo, a dialect of Aramaic, the language of Jesus that is still used in local church services.

To the west of the centre, Estel boasts one specific attraction which is a Cultural Centre housing typical local artefacts including some of the massive wooden “tahts (thrones)”.

Just beside one of the Gelüske Han’s entrances is a shop selling Siirt kilims, stripy blankets that are, despite their name, hand-woven on site. They make cheap and excellent souvenirs, as do the home-made red Suryani wines.

Sleeping

Kasr-ı Nehroz, Midyat. Tel: 0482-464 2525

Matiat Hotel. Tel: 0482-462 5920 (2km out of town on Mardin road)

Transport info

The nearest airport is in Mardin whence there are regular dolmuşes to Midyat. You can also get here easily by bus from Diyarbakır.

The minibus terminal in the old town saves visitors a walk or taxi ride from Estel. If you want to stay in Estel there is a second bus station there where dolmuşes arriving from Mardin stop before going on to the old town.

Buses ply Cumhuriyet Bulvari, the road that links Estel with the new town. Hop on one to avoid a long, dull walk to the centre.

Day trip destinations