At 5 o’clock in the morning, before most people have even opened their eyes, Dudu and her 20-year-old daughter Hatice are already hard at work in the Isparta rose fields. Wearing fingerless gloves to protect their hands and sacks tied like aprons around their waists, they work methodically along the rows, plucking the small pink blooms of the Turkish damask rose (Rosa damascena triqintapetala), one of only five rose species in the world that can be used to make rose oil. The roses must be picked early in the morning when their scent is at its strongest, and Dudu, Hatice and the many other women like them form the backbone of an industry worth a fortune to Isparta.

Picking roses sounds quite romantic until you actually try it, whereupon its less glamorous side is quickly revealed. The gloves may protect the women from the thorns but nothing can save them from having to bend for the blooms on the lowest branches and stretch for those on the highest. At first light the sun is pleasantly warm but by 9am the sweat is already trickling down their backs and work finishes for the day. On rainy mornings the sandy soil thickens into mud. And then there are the bees. As the sun gets into its stride so do these anti-social insects who buzz jealously around the flowers. “Last year I was stung by a bee and my whole hand swelled up,” Hatice tells me. “My mother calls their sting a kiss but I had an allergic reaction and couldn’t work for two days.”

Dudu has been picking roses for five years, Hatice for only two. Together they pluck between 45 and 70 kilograms a day, which sounds a lot until you learn that it takes 40 kilograms of petals to make just 10 millilitres of rose oil. Their labour earns them between YTL15 and YTL25, and by the time they go home for breakfast it looks as if a plague of locusts has worked its way through the field. After them, a second set of women go through the sacks and remove all the pieces of stalk.

“You can sit down to do that,” Hatice says which makes the work a good deal less onerous. Inevitably, however, the pay is lower, so she and her mother prefer to brave the bee stings.

Isparta’s roses are mainly grown in small family-owned fields. They flower between mid-May and mid-June which is peak season for the rose industry. It is also the time when Joanna Klein Woterink, the vivacious Dutch “Queen of the Roses” brings study groups to Turkey to learn how rose oil is extracted from the petals.

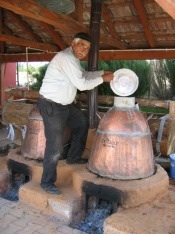

I meet Joanna at the family-owned Sebat factory in Senir on the shores of Lake Burdur. An aromatherapist by profession, she first came to Turkey’s Lake District in 1998 and quickly fell in love with the Isparta rose. In her wanderings around local villages she found some people still extracting rose oil in the traditional way using large copper stills. Impressed, she approached the Sebat factory where Hasan Ali Kinacı, the owner’s son, readily agreed to install a still in the grounds. Nowadays it is used to make rose oil in the old-fashioned way on two days of the week.

I find Joanna at the factory with a group of half-a-dozen Dutch rose enthusiasts. What for Dudu and Hatice is just work is for them a chance to take a hands-on holiday. “We’re all very tired,” Joanna says apologetically, “Because we got up early to help with the picking.”

While group members retreat to a village house to sleep off their exertions, Joanna guides me through the traditional distillation process with the help of Sami, an elderly villager who learned to make rose oil in his childhood. Now he has come out of retirement to pass on his knowledge to these rather unlikely visitors from Europe.

The process of water vapour distillation turns out to be surprisingly straightforward. First roses are placed inside the stills with plenty of water. Then they are heated slowly to just below boiling point. The steam given off is directed into pipes running through a trough of cold water so that it cools and condenses. As it drips slowly down into a glass jar, the precious rose oil forms a paper-thin layer on top of a much larger quantity of rose water. Then the liquid is returned to the still and reheated, and the whole process begins again. This second distillation is the one that ends up in the shops as rose oil for aromatherapy and rose water for skin care and food flavouring.

Of course even at Sebat most production is carried out in modern factory conditions. I watch as big sacks stuffed with roses arrive in trucks to be offloaded onto conveyor belts and whisked into the factory. There a great sea of pink petals spreads out across the floor. “If you leave the roses inside the sacks they quickly heat up and start to ferment,” Joanna explains, her sensitive nose twitching at the very thought. To prevent this from happening the roses are spread out on the floor to air until their turn comes for distillation. It makes an extraordinary sight and the scent is almost overwhelming. “Sometimes people in my groups are reduced to crying by the power of the roses,” Joanna says as she sweeps up great handfuls of petals.

The modern rose-oil factory resembles a milking parlour, all stainless steel vats and pipes to distil the products as quickly and efficiently as possible. In his airy office nearby I meet Hüseyin Kınacı, the man behind Sebat. He and his jolly wife, Faden, tried their hands at all sorts of other businesses before finally settling for rose oil. Almost twenty years later, they and their sons run a thriving concern that exports to Europe and the USA. Mr Kınacı tells me that he has 43 people working for him at the height of the season, although only 16 of them work year round; the rest are farmers and builders topping up their income when the rush is on. Recently he has noticed a big increase in the popularity of organic produce. “When we started,” he says, “organic roses formed a very small part of the business. Now it is roughly 50-50.”

Sebat is a relatively small operation but elsewhere in the Lakes there are much bigger factories including the four owned by the Rose Cooperative (Gülbirlik), a company that started business in 1954 and now runs to four separate sites. At the factory I meet general manager Tangut Çetin. He tells me about Gülbirlik’s flourishing cosmetics business, Rosense, which exports perfumes, shampoos, creams and lotions to countries as far afield as Azerbaijan and Vietnam. “The Arabs are especially fond of roses,” he says, “so we also do a lot of business with them.”

Until fifty years ago when it was replaced in popularity by lemon cologne, many Turks used rose water as a scent with which to sprinkle the hands of guests. Mr Çetin hands me a glass of blush-pink drink. “In Ottoman times rose-flavoured şerbet was also very popular,” he says. “Then Coca-Cola came along and everyone stopped drinking it. This year we have started making gül şurubu (rose syrup). We hope it will be popular especially with people who don’t want to drink alcohol.” Served with ice, the syrup turns out to be deliciously refreshing. They could be onto a winner, I think.

Isparta high street is one long homage to the rose. Gülbirlik has a shop there, a classy place, full of skin creams and body lotions in tasteful Clarins-style packaging. Elsewhere, however, everything is bright Barbie pink. Shop windows positively glow with everything rosy and the shelves are weighed down with rose cologne, rose soap, rose lokum (Turkish delight), rose candles and rose jam. The scent is overpowering and some of the colouring remarkably synthetic.

Back at Sebat, Joanna’s rose study group have recovered from their morning’s exertions and are learning to make jam under the supervision of Mrs Kınacı. Under close observation she stirs sugar and water into a saucepan, adds lemon and then feeds in the rose petals. The end product is sweet and thin, and very tasty provided you don’t mind the slightly unnerving sight of rose petals on your bread.

For a few brief weeks the Lake District lives and breathes roses. Every other woman I bump into seems to be helping an aunt or cousin pick the harvest and they smile at the scratches on my arms, a badge of honour which marks me out as one of them. Out in the fields Dudu and Hatice have just a few more days to fill their apron pockets with roses. Then another season will come to an end and Dudu will move onto the cherries while Hatice returns home to prepare tea and dream of her wedding day.